Jordan-Hahn Decomposition

Jordan-Hahn decomposition is one of the most important theorem in measure theory but its proof is both lengthy and hard to understand, at least for beginners. In this post, I want to give an intuitive understanding on its proof to illustrate why it constructs a set like that and what it is doing.

Jordan-Hahn decomposition states as follows,

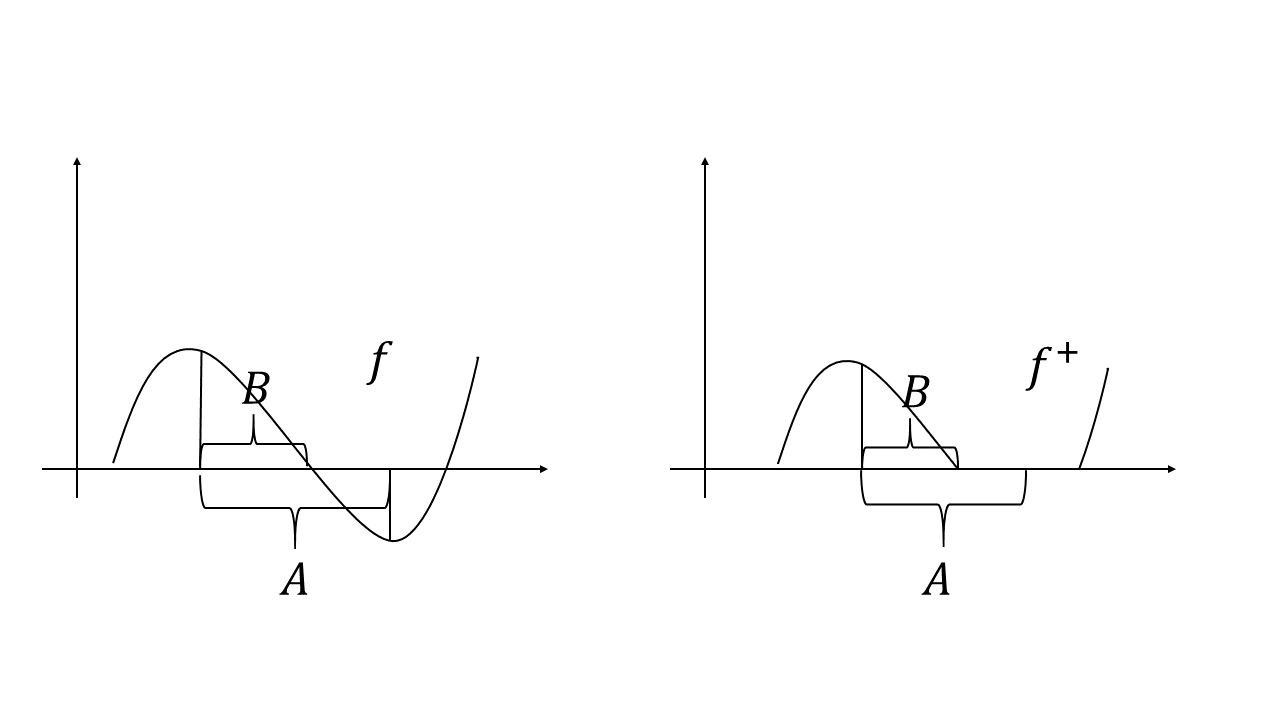

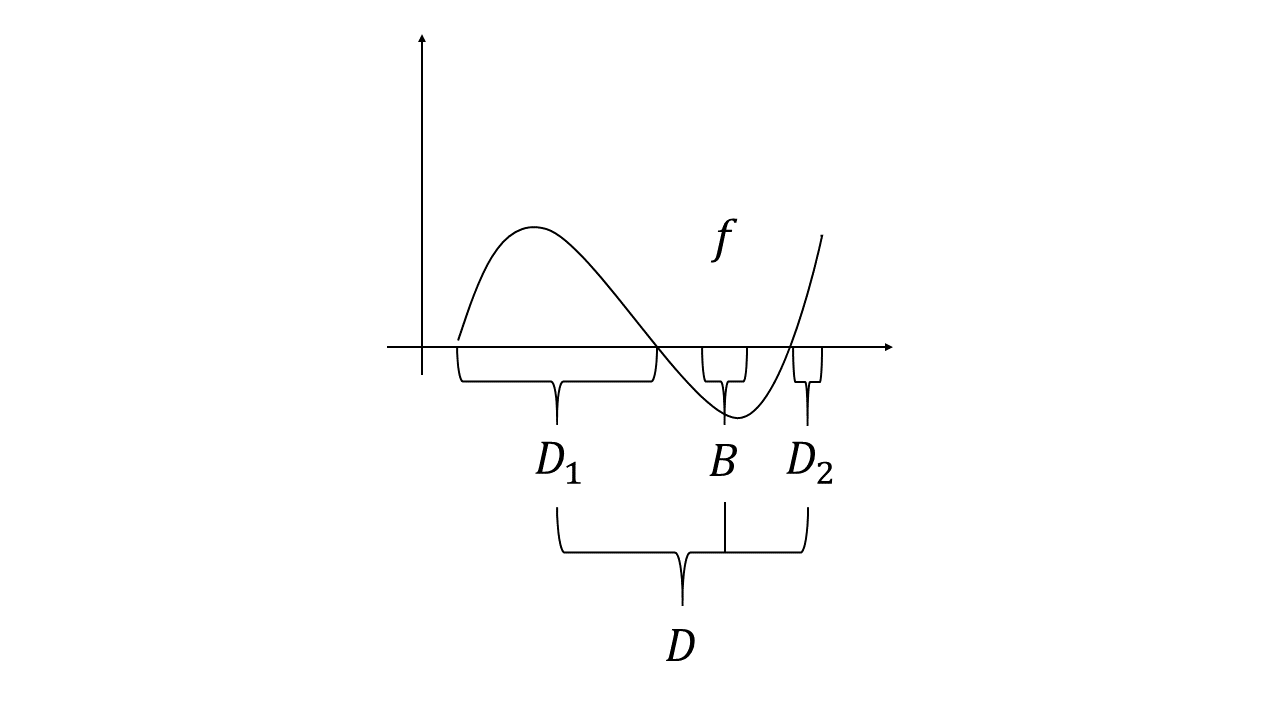

Let $\nu$ be a signed measure on $(\Omega, \mathcal{F})$. Then it has a decomposition $$\nu = \nu^+ - \nu^- $$ where $$ \nu^+(A) = \sup \{\nu(B)|B\subset A, B \in \mathcal{F}\} $$$$ \nu^-(A) = \sup \{-\nu(B)|B\subset A, B \in \mathcal{F}\} $$ and both $\nu^+$ and $\nu^-$ are measure and one of them is a finite measure. Furthermore, there exists a set $D\in \mathcal{F}$ s.t. $$ \nu^+(A) = \nu(A\cap D),\ \nu^-(A) = \nu(A\cap D^c) $$

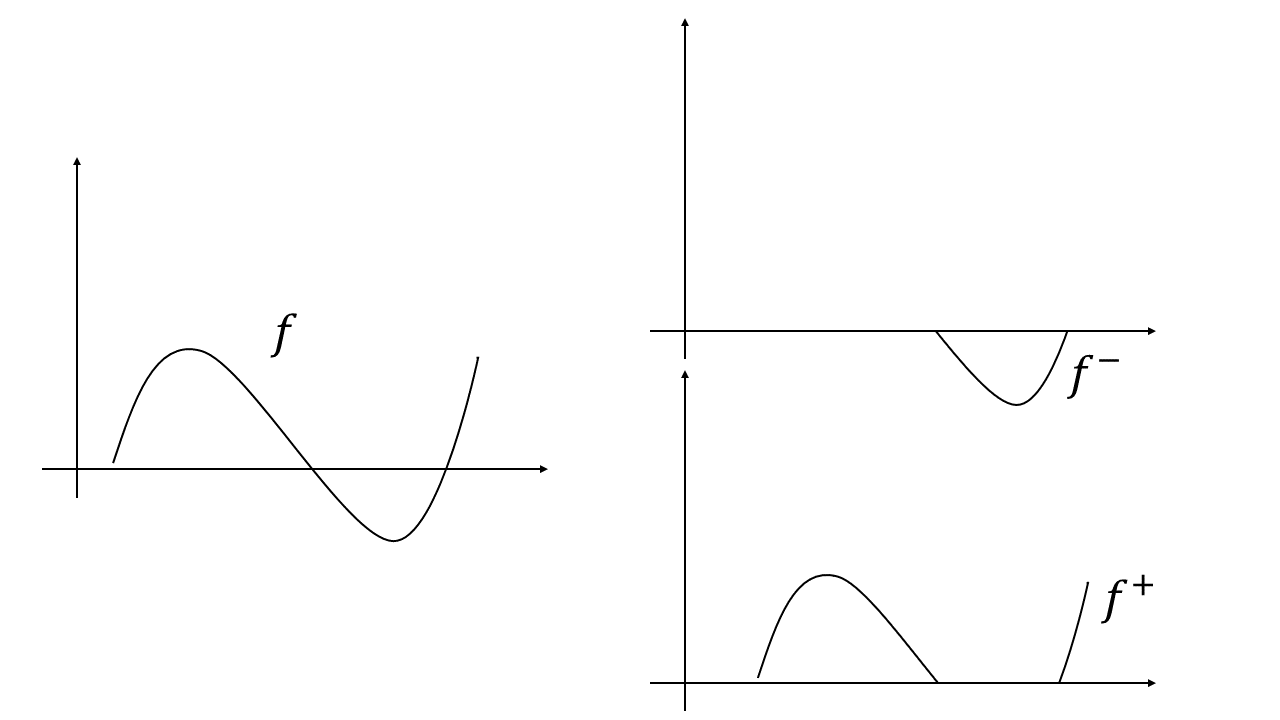

Before we move on to its proof, let’s consider a special case - indefinite integration. Let $f$ be a measurable function on $(\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mu)$ and define the $\nu$ as follows

$$

\nu(A) = \int_{A} f d\mu

$$

Clearly, it is a signed measure and it has a natural decomposition

$$

\nu(A) = \int_{A} f^+ d\mu - \int_{A} f^- d\mu

$$

Now we only have one tool to do this - measure (or integration). Note that in the indefinite integration case, we have if $\forall B \subset A\in \mathcal{F}$, $B\in \mathcal{F}$, $\int_B fd\mu \geq 0$, then $f \geq 0$ on $A$. Here we can translate the integration to measure i.e. if $\forall B \subset A\in \mathcal{F}$, $B\in \mathcal{F}$, $\nu(B) \geq 0$, then $f \geq 0$. The picture is clear now. We just need to find those set s.t. every subset of it has positive measure. So we define $$ \mathcal{B} = \{B\in \mathcal{F} | \forall C\in \mathcal{F}, C\subset B, \nu(C) \geq 0\} = \{B\in \mathcal{F} | \nu^-(B) = 0\} $$ We can be confident to say that this $\mathcal{B}$ captures all part of “$f^+$”. Our next task is to find the real support of “$f^+$” i.e. a $N\in\mathcal{B}$ s.t. $f^+ = 0$ on $N^c$. There are two way to do it: (i) find the set with the biggest measure; (ii) find the biggest set. One can refer to Meature Theory by Dr. Jiaan Yan to see how to do the first one. Here I will use the Zorn Lemma to go through the second one. Define the partial order on $\mathcal{B}$ to be $\subset$. Since $\mathcal{B}$ is closed under union (why?), by Zorn Lemma, we can find the biggest set $D$. So we have answered the two questions mentioned above.

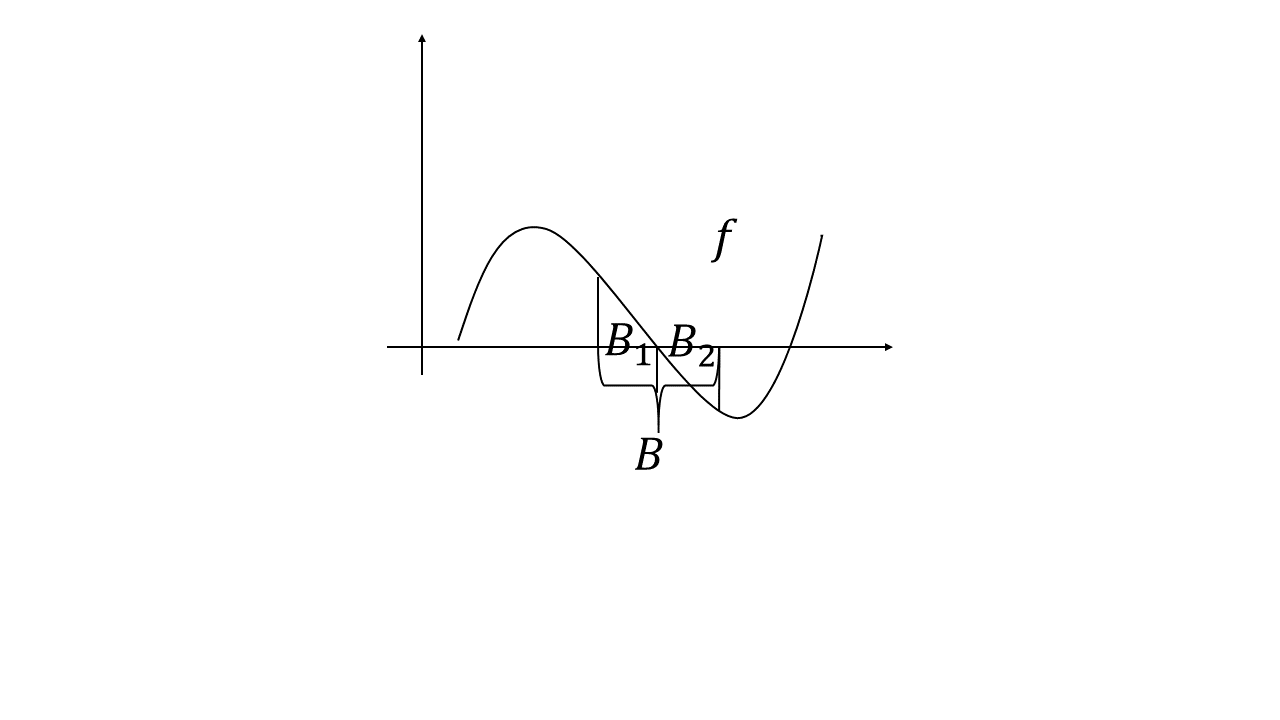

Our last task is to show that $\nu^+(A) = \nu(A\cap D)$, which is intuitive based on our discussion above. Before moving on, we need to test whether the $D^c$ capture the support of $f^-$. Intuitively, if there is a $B \subset D^c$ s.t. $\nu(B) > 0$, we can show that $\nu^- (B) > 0$. If not, there will be a contradiction to our construction of $D$, which can be illustrated by the following figure.

So far, we have shown that $\nu \geq 0$ on $D$ and $\nu \leq 0$ on $D^c$. The final step, $\nu^+(A) = \nu(A\cap D)$, can be directly proved by the definition of $\nu^+$ and $\nu^-$. Thus we completes the proof of the John-Hahn decomposition.